During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that requiring research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well-thought-out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

When researching new knowledge or scientific material, it can be tricky to find reliable sources. There will be confounding information all over the place, and sorting through to find the best sources is important. Having credible information is pertinent for any profession in which advice is given to clients. Massage Therapy falls under this professional advisory because the therapist will want to impart knowledge and information to their clients that is reliable and accountable of truth. Research articles that have been peer-reviewed or published in scholarly journals are a valid source to find material for a massage profession, even though they can still hold bias. They are valid because these articles are reviewed by experts in the field of study that the author is writing about; and prior to an article being published in a journal, it must be rigorously evaluated and revised. To determine whether or not the information one has researched about is applicable or correct, it must be found and published as a scholarly article in an established journal or magazine, or by a credible source with reputable evidence. Otherwise, it is easy to find any random article off the internet, those of which tend to hold a lot of misinformation, biased reports, or false claims. Research is important in a massage therapy profession because it is imperative to present reliable advice to a client, with a quality of critical and logical thinking. Examining data and study methods from many different credible viewpoints will help ensure a comprehensive approach to answering questions, issues, or problems that may present themselves with clientele. When sorting through articles to find information about a research question, it is essential to look under scholarly sources, such as National Institutes or a government website for scientific research. When looking for information to answer the research statement I was interested in, "Does massage help rid the body of cellulite," I went to PubMed and Google Scholar. After sifting through various articles to find those that apply to my question at hand, I found that massage alone does not rid the body of cellulite (otherwise known as gynoid lipodystrophy) and that one must have other contributing treatments to help reduce signs of cellulite.

When searching to find answers to my research statement, I found three articles that discussed relative to my research findings. The first article was a longitudinal evaluation for the treatment of gynoid lipodystrophy using manual lymphatic drainage. The study included 20 women from 20 to 40 years of age, 15 of which completed the study. Using an open, prospective, intervention method, once a week for fourteen sessions, these women received manual lymphatic drainage on their lower limbs and buttocks. The results concluded that manual lymphatic drainage, as an isolated approach to cellulite management, was safe but not effective. These women were observed to have a significant improvement in their quality of life, even though massage alone was not able to reduce their cellulite. It is necessary to have further research studies completed that are randomized, controlled or comparative studies to test whether or not manual lymphatic drainage is effective for cellulite control. The second and third articles that pertained to my research statement discussed the use of mechanical massage, which seemed to have better results for cellulite management than manual massage alone.

When researching the findings of the statement I chose to examine, I found more information about mechanical massage techniques than I did for manual massage alone. The second article I chose assesses the "Effects of mechanical massage, manual lymphatic drainage and connective tissue manipulation techniques on fat mass in women with cellulite." The objective of this study was to compare and evaluate the effectiveness of three noninvasive treatment techniques for patients with cellulite, looking at fat mass and regional fat thickness. Sixty subjects were divided into three randomized groups, one for each different treatment technique, which is indicated in the title of the article above. After the treatments, all groups had improvement in thinning of subcutaneous fat, but it does not state if any improvement were made directly relating to cellulite. The article concluded that all treatment techniques were effective in decreasing the values of regional fat for patients with cellulite. In the third article I examined, efficient treatment for cellulite was found using a combination of bipolar radio frequency (RF) and intense infrared light (IR) with mechanical massage and suction. This split study evaluates the efficacy of the combined system through which various treatments were performed on areas located in the buttocks that had cellulite. The study used one buttock as the untreated control, while the other was used for treatment of 12 sessions of 30 minutes each. There were ten patients and sessions were conducted over a period of 12 weeks, twice a week. The treatment session results concluded that combined RF, IR and mechanical massage and suction produced overall improvement in skin condition and cellulite appearance, was complication free and that further treatment sessions could lead to lasting results. The authors recognized that a small number of participants produce limited statistical power, and further studies are warranted with a larger patient population. Out of all three articles I examined, this third article had the most qualifying outcomes about the research statement I was interested in.

The research findings I assessed support the statement I examined in some ways, and in other ways, they did not. When answering the question, does massage rid the body of cellulite, it seems the straightforward answer would be no. Massage alone does not rid the body of cellulite, although massage, combined with other mechanical massage manipulation techniques, does seem to have more of an effect for improvements in cellulite reduction. The implications that this understanding has for my own knowledge base and practice is that I now know what to tell clients if they ask if massage will help reduce their areas of cellulite. I will be able to explain that massage alone does not seem to have the evidence to back up this claim but that there have been other studies using massage manipulation techniques that do seem to have significant results. This effect matters to me because I wish to be able to tell clients credible information with significant evidence to back up the claims that are asked about. In my massage beliefs and professional beliefs in general, it is important to me to think in a critical and logical way about the many health claims that appear in this field of work. In the end, we still do not know the best way to effectively reduce cellulite in the body, and further studies with larger randomized groups are necessary.

Citations

Bayrakci Tunay, V., Akbayrak, T., Bakar, Y., Kayihan, H. and Ergun, N. (2010). Effects of mechanical massage, manual lymphatic drainage and connective tissue manipulation techniques on fat mass in women with cellulite. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 24: 138-142. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03355.x

Caballero, N., Herrero, M., Romero, C., Ruiz, R., Sadick, N.S., and Trelles, M. (2009). Effects of cellulite treatment with RF, IR light, mechanical massage and suction treating one buttock with the contralateral as a control. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy, 10(4), 193-201. doi:10.1080/14764170802524403.

Schonvvetter, Bl, Soares, J.L.M., and Bagatin, E. (2014). Longitudinal evaluation of manual lymphatic drainage for the treatment of gynoid lipodystrophy. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia,89(5), 712-718. http://doilorg/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143130

During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that require research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Based on surveys by the American Massage Therapy Association, one of the primary motivations today for people seeking massage is for health and wellness reasons (AMTA, 2017), clearly indicating that massage therapy is becoming accepted as a form of healthcare. Yet, under the umbrella of the term "massage therapy," many modalities exist that claim the ability to help lessen the discomfort of numerous conditions. The primary means that we, as a society, have to attempt to validate the claims about massage therapy is the application of scientific research methodology. However, our current system relies on large amounts of money being funneled into research for patentable substances that, if successful, provide a large financial reward to the patent-holding creator. As massage cannot be patented past a registered trademark for someone's name, limited funding is available for the research. Thankfully, though, as massage gains in popularity, there is a grassroots push for more information and continued research into various types of massage therapy.

Within scientific research there is a hierarchy of journal articles: randomized clinical trials (RCT's)-specifically, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies--are considered the "gold standard" by the medical establishment. In this type of study (ideally), the variables are stringently controlled and bias is almost completely eliminated. Then the written results undergo peer review so that any potential shortfalls in the process can be found and remedied. The goal is to create a situation in which the experiment can be duplicated by any other researcher, thus confirming the findings and verifying that the results apply to the majority, that is, that the results are statistically significant to a specific percentage of a group and that the results are not random.

There are a number of other types of research articles that rank "below" the RCT but are still considered valid research (and are accepted into the peer-review process of a journal), or are at least indicative of an area of continued study and where RCT's should be designed and undertaken. These include systematic reviews, cohort studies, case-control studies, case reports and pilot studies. Today, due to the efforts of many people, a quick search for "massage therapy" in PubMed shows a large variety of these types of articles, although some modalities and some types of research have received much more attention than others, and some modalities lend themselves to the scientific process more readily than others.

I believe that all of these types of studies are valid when looking for studies to expand our understanding of how massage works and what we should offer our clients, as long as we understand that nothing will ever be one hundred percent effective. Ultimately, there is no perfect piece of research. That's the one true absolute in scientific analysis. The "gold standard" is based on statistical analyses that calculate how the experiment affects the group or cohort. It's impossible to run an experiment on the entire population of the planet. By design and definition, a study has to be performed on a representative group, and even then the goal is to find a "treatment" that affects the majority of the group rather than all of the group, because there will always be "outliers": those who don't respond when it is effective for the majority, or those who will be affected when the majority aren't. In other words, statistics deal with group results while the individual is concerned about the response of themselves or their loved ones. This is the fundamental struggle in utilizing research in providing services for individuals.

However, all of these types of research work well together: case studies build case reports that can then be built into case-control studies. When the subjects are followed for a period of time, a cohort study is produced. Pilot studies initiate work into new sub-areas and systematic reviews look at the results of various studies. All of these together build a comprehensive understanding of an area as well as point to new experiments to pursue. It all adds to our knowledge base and I believe that's the best result.

Given that research about massage therapy is increasing, it would probably be wise for any therapist who wishes to be involved in research to take a "Statistics for the Social Sciences" type class at a local community college or university. It makes understanding research abstracts much easier, as well as assisting the therapist in spotting the weaknesses in writing about new research that is very common in today's internet connected world. In an ideal world, there would be many RCT's with cohorts numbering in the thousands, but given the realities of research, I'm happy when they number over fifty. I also find case studies very interesting precisely because they discuss how one person was helped with a specific treatment and that's where research starts.

As massage therapy encompasses so many modalities, and the technological advances in various forms of diagnostics and measurements continue at a brisk pace, I believe that research in massage therapy will continue to grow. It expands our knowledge of what we do and how we can assist our clients in their goals. It also furthers the standing of massage therapy as a method of health care. As there are still those who criticize and "debunk" various aspects of massage therapy, rightly or wrongly, research is necessary to find the truth.

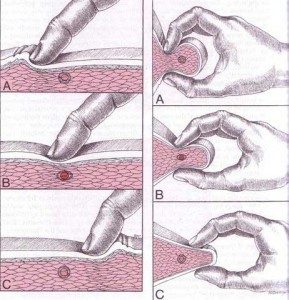

In examining the statement "ischemic compression for trigger points should be done as deep and hard as possible" with regard to current research, it's useful to look at the verity of the statement first. My first concern about this statement is that it's an absolute. While the word "always" is not in the sentence, it's implied. As I mentioned earlier, absolute statements about the care of others are dangerous as they are unprovable, and adhering to blanket statements about the care of individuals makes you blind to possible exceptions, which in turn leaves you open to charges of client neglect. Secondly, trigger points, by definition, are  "hyperirritable:" they're painful when subjected to pressure, one of the diagnostic criteria as listed in Travell and Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, the authoritative work in the field. If a massage therapist simply puts as much pressure on a trigger point as is possible, it hurts. The therapist can also activate the nociceptive reflexes of their client which will cause the client to tense up and pull away as they attempt to protect themselves. This can result in the loss of the client at least, as well as potentially injuring a client, both situations that an ethical therapist hopes to avoid. So, the statement is questionable to begin with.

"hyperirritable:" they're painful when subjected to pressure, one of the diagnostic criteria as listed in Travell and Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, the authoritative work in the field. If a massage therapist simply puts as much pressure on a trigger point as is possible, it hurts. The therapist can also activate the nociceptive reflexes of their client which will cause the client to tense up and pull away as they attempt to protect themselves. This can result in the loss of the client at least, as well as potentially injuring a client, both situations that an ethical therapist hopes to avoid. So, the statement is questionable to begin with.

But in looking at available research studies on ischemic compression and trigger points, there does seem to be agreement on how to apply ischemic compression, although what's used in the papers I've read is something of a combination of what's suggested by Simons and Travell. In the 1st edition of The Trigger point Manual, published in 1983, both ischemic compression and deep stroking massage are mentioned as possible manual treatments for trigger points, and in a 1987 monograph Simons repeats that "pressure is applied directly on the spot of greatest tenderness (the TP) with a steady moderately painful (tolerable) pressure." This is to be held for 15 seconds to one minute (Simons, 1987). It is perhaps the reading of this that encouraged some therapists to adopt a use of "as deep and hard as possible" even though, in my opinion, that would be a misinterpretation given the words "moderately" and "tolerable."

However, in the 2nd edition of the Trigger Point Manual, published in 1999, their recommendations change, even stating that they prefer to call it "trigger point release therapy" rather than ischemic compression, and it's described as a "barrier resistance technique" to underscore a more moderate approach (Simons et al., 1999). They recommend that the therapist use a moderate pressure on the center of the trigger point until the therapist encounters a resistance that they label "the barrier." The pressure is held until the resistance decreases somewhat, and then the pressure is increased until it again meets the barrier. Again this is maintained until the barrier releases or "let's go" under the finger. This technique is specifically recommended because it is painless (Simons et al., 1999). Again, there is nothing here to suggest "as hard and deep as possible."

When looking at several studies completed since the publication of the 2nd edition, the accepted technique for applying ischemic compression seems to be somewhere in the middle of these two techniques. Generally speaking, the practitioner would apply pressure to the center of the trigger point until pain was first felt, usually described by the participant as a 7 on a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 being the most painful. The pressure was held until an initial decrease in discomfort was experienced, then the pressure was increased to the tolerance threshold again and held until there was another decrease in discomfort, usually from 15-90 seconds (Abu Taleb et al., 2016, Cagnie at al., 2013, de las Penas et al., 2006).

A pilot study comparing the effects of ischemic compression and transverse friction massage on active and latent trigger points on a study group of forty people, published in 2006, utilized this procedure for the ischemic compression part of their testing. This was compared to transverse friction applied slowly with pressure that created a tolerable pain for 3 minutes. Interestingly, both methods achieved statistically significant results based on measurement of the decrease in the pain pressure threshold (PPT) (de las Penas et al., 2006).

A cohort study in 2013 that followed the treatment of nineteen office workers treated with ischemic compression for upper trapezius trigger points for 8 sessions over 4 weeks (2 sessions per week), utilized the same protocol. At the end of the 4 weeks/8 sessions there was a statistically significant decrease in the PPT as well as at a 6-month follow-up, and there was also a significant increase in mobility and strength (Cagnie et al., 2013).

More recently a clinical study was completed that examined the results of manual pressure release (ischemic compression) compared to that delivered by an algometer with sham ultrasound as the control (Abu Taleb et al., 2016). Instead of just using the algometer to measure the pre- and post-treatment PPT they also used it (with the addition of a piece of cloth for comfort) to administer the manual pressure release to the trigger point (the APR group) along with sham ultrasound. The second group received similar treatment from a trained therapist (the MPR group) along with sham ultrasound while the third group (the US group) only received the sham ultrasound. While there was no significant difference between the 3 groups post-treatment for the PPT, the APR group had a statistically significant increase in passive side-bending range of motion.

While all three of these studies seem to indicate that manual pressure release (ischemic compression) has positive results for trigger point treatment, there are other studies that show less consistent results. However, what all of these studies do indicate is that the accepted protocol of ischemic compression on trigger points is to apply pressure to the trigger point to a level of tolerable pain for the client, hold until that decreases, then increase and hold again until another decrease occurs, and then repeat the procedure another 1-2 times to equal 90 seconds. Not one of these experiments utilizes ischemic compression that is "as deep and hard as possible."

When Dr. Janet Travell and Dr. David Simons first published their Trigger Point Manual in 1983, it was an effort to create a compendium of their work and research into the treatment of trigger point pain. Primarily meant as a resource for physicians and physical therapists, it mainly discusses the use of methods such as trigger point injection and "stretch and spray" that can easily be employed in office settings. However, their mention of ischemic compression as a manual therapy really opened the door to the therapuetic use of massage in this area, given how many people dislike needles. And, while the research into manual pressure release as a viable means to treat trigger points is somewhat limited, as most of the research examines dry needling and injections, I believe the existing research indicates that it's at least of some value. However, I also think that it's very important to use the protocol that is consistently recommended and used by these research articles in only applying pressure to a tolerable level of pain rather than following the mandate that it "should be done as deep and hard as possible."

References:

Abu Taleb W., Rehan Youssef, A. and Saleh, A. (2016) "The effectiveness of manual versus algometer pressure release techniques for treating active myofascial trigger points of the upper trapezius," J Bodyw Mov Ther, 20(4), pp. 863-869.

AMTA (2017) Massage Therapy Industry Fact Sheet: American Massage Therapy Association. Available at: https://www.amtamassage.org/infocenter/economic_industry-fact-sheet.html (Accessed: May 16 2017)

Cagnie, B., Dewitte, V., Coppieters, I., Van Oosterwijck, J., Cools, A. and Danneels, L. (2013) "Effect of ischemic compression on trigger points in the neck and shoulder muscles in office workers: a cohort study," J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 36(8), pp. 482-9.

de las Penas, C.F., Alonso-Blanco, C., Fernandez-Carnero, J., and Miangolarra-Page, J. (2006) "The immediate effect of ischemic compression technique and transverse friction massage on tenderness of active and latent myofascial trigger points: a pilot study," Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 10(1), pp. 3-9.

Simons, D.G. 1987. Myofascial Pain Syndrome Due to Trigger Points. In: Association, I.R.M. (ed). Gebauer.

Simons, D.G., Travell, J.G., and Simons, L.S. (1999) Travell & Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: the Trigger Point Manual. 2nd edn. (2 vols). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that require research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Preface:

Does massage therapy flush lactic acid from the muscles? Since I began working out and trading massage therapy I have heard that this is an important benefit of massage therapy. A good massage certainly feels wonderful after a strenuous work out. Who wouldn’t want that? Is there a mechanical action reaction from compressive and Effleurage, or Swedish touch that directly “flushes” the molecular compound called Lactic Acid “out” of each muscle cell? Where does this Lactic acid come from? Is it a result of a natural metabolic process as the cell produces energy during action? What happens to this Lactic acid and why? What could be the benefits of flushing or releasing lactic acid from the muscle? Where would it go? Is there a co relation to just feeling good, and a reduction of lactic acid in the muscle tissue? Is the pain associated from strenuous exercise a result of lactic acid in the muscle cells?

As professional massage therapists, it is incumbent upon us to inform the client of possible outcomes from massage therapy. This we do in a limited fashion in the assessment phase of the session. We ask the client what their expectations are from receiving massage therapy. We may be asked this question “Will this body work release lactic (and “toxins) from my cells?” To make an uninformed claim could lead to unintended consequences and a probably dissatisfied client whose expectations were not met, or are unobtainable. To build professional integrity we must advise the client with valid and substantive claims that meet their expectations. Claims that we know are true to the best of our knowledge. Our knowledge backed up by science and evidence. “We all have heard, or know that…..” is anecdotal and may lead the client to frustration and disappointment from the service. This is the last thing a professional Massage Therapist wants from their work.

Massage Therapy as an industry must have a system of ethics that adheres to information backed up by science just as the Medical industry is grounded in science. This derives from peer review papers based upon empirical scientific method, research, statistical evaluation as well as consensus of the industry. My intention with this paper will be to resolve some of the above questions in order to make an informed and valid statement regarding lactic acid and how massage therapy will help or not help the “build up” and release of this biological component of our metabolism.

I chose this topic because “I just do not know” the truth of this assertion. I would feel a lack of integrity in the informing of a client something that I could not validate. All things are connected and each part adds to or detracts from the building of the Massage Therapy industry. Our highest goal is to treat each client with the highest professional regard and respect for the best and greatest outcomes, every time a human being comes to us for healing or to just feel better. Knowledge is the basis of being a Professional, and this is my goal.

Thesis Statement

The current science indicates that massage does not actively “de tox” muscle tissue by “pushing out” from the muscle cells. I think that there is some effect as yet undefined but correlating to Well Being, feeling better as a result of massage therapy that may allow a homeostatic effect that enhances in the metabolic process of lactic genesis.

Outline

What is Lactic Acid?

Lactic acid is an organic compound with the formula CH3CH(OH)COOH. In its solid state, it is white and water-soluble. In its liquid state, it is clear. It is produced both naturally and synthetically. With a hydroxyl group adjacent to the carboxyl group, lactic acid is classified as an alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA). In the form of its conjugate base called lactate, it plays a role in several biochemical processes.

In solution, it can ionize a proton from the carboxyl group, producing the lactate ion CH

3CH(OH)CO−

2. Compared to acetic acid, its pKa is 1 unit less, meaning lactic acid deprotonates ten times more easily than acetic acid does. This higher acidity is the consequence of the intramolecular hydrogen bonding between the α-hydroxyl and the carboxylate group.

Lactic acid is chiral, consisting of two optical isomers. One is known as L-(+)-lactic acid or (S)-lactic acid and the other, its mirror image, is D-(−)-lactic acid or (R)-lactic acid. A mixture of the two in equal amounts is called DL-lactic acid, or racemic lactic acid.

Lactic acid is hygroscopic. DL-lactic acid is miscible with water and with ethanol above its melting point which is around 17 or 18 °C. D-lactic acid and L-lactic acid have a higher melting point.

In animals, L-lactate is constantly produced from pyruvate via the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in a process of fermentation during normal metabolism and exercise. It does not increase in concentration until the rate of lactate production exceeds the rate of lactate removal, which is governed by a number of factors, including monocarboxylate transporters, concentration and isoform of LDH, and oxidative capacity of tissues. The concentration of blood lactate is usually 1–2 mmol/L at rest, but can rise to over 20 mmol/L during intense exertion[4] and as high as 25 mmol/L afterward.[5]

In industry, lactic acid fermentation is performed by lactic acid bacteria, which convert simple carbohydrates such as glucose, sucrose, or galactose to lactic acid. These bacteria distilled water, generally in concentrations isotonic with human blood. It is most commonly used for fluid resuscitation after blood loss due to trauma, surgery, or burns. can also grow in the mouth; the acid they produce is responsible for the tooth decay known as caries.[6][7][8][9]

In medicine, lactate is one of the main components of lactated Ringer's solution and Hartmann's solution. These intravenous fluids consist of sodium and potassium cations along with lactate and chloride anions in solution with distilled water, generally in concentrations isotonic with human blood. It is most commonly used for fluid resuscitation after blood loss due to trauma, surgery, or burns. (Wikipedia)

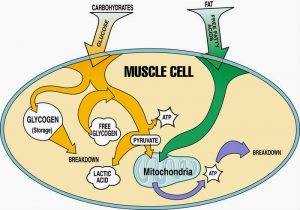

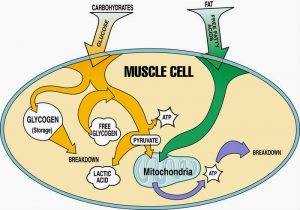

Exercise and lactate

During power exercises such as sprinting, when the rate of demand for energy is high, glucose is broken down and oxidized to pyruvate, and lactate is then produced from the pyruvate faster than the body can process it, causing lactate concentrations to rise. The production of lactate is beneficial because it regenerates NAD+ (pyruvate is reduced to lactate while NADH is oxidized to NAD+), which is used up in oxidation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate during production of pyruvate from glucose, and this ensures that energy production is maintained and exercise can continue. (During intense exercise, the respiratory chain cannot keep up with the amount of hydrogen atoms that join to form NADH, and cannot regenerate NAD+ quickly enough.)

The resulting lactate can be used in two ways:

However, lactate is continually formed even at rest and during moderate exercise. Some causes of this are metabolism in red blood cells that lack mitochondria, and limitations resulting from the enzyme activity that occurs in muscle fibers having a high glycolytic capacity (Wikipedia)

Is the pain of strenuous exercise caused by Lactic Acid genesis?

In a Viewpoint article, Lindinger (2011) commented that ‘…lactate accumulation is a necessary evil associated with high speed’. Added commentary included, ‘That such high rates of lactate production can benefit performance, and yet such high lactate concentrations impair performance (Cairns, 2006), remains a conundrum of exercise physiology’. It is important to correct several immediate and underlying aspects of this interpretation of metabolic biochemistry and the data from the original research of Kitaoka et al. (2011).

Repeated intense muscle contraction can cause high rates of lactate production, with greatest rates occurring in fast-twitch glycolytic (type IIb) muscle as explained by Lindinger (2011). The long history of lactate, lactic acid and exercise-induced fatigue, even to the present time, has been tainted by erroneous interpretations of a detrimental view towards inter-relationships between muscle lactate production, acidosis and muscle contractile failure (Robergs et al. 2004, 2005; Cairns, 2006; Brooks, 2010). However, it is clear from application of fundamental principles of organic chemistry, enzyme kinetics and metabolic biochemistry that muscle lactate production is an essential feature of repeated intense muscle contractions, and that without lactate production such repeated contractions could not occur (Robergs et al.2004).

Why is lactate production essential? Muscle must produce lactate during intense contractions and/or when there are insufficient mitochondria and/or oxygen, because this remains the only alternative (non-mitochondrial) means to regenerate cytosolic NAD+. Muscle lactate production is therefore a rapid means to maintain cytosolic redox, which sustains phase II of glycolysis, which in turn sustains glycolytic ATP regeneration. Lactate production also metabolically consumes an H+ ion, which means that it directly opposes metabolic H+ release and cellular acidosis, which in turn means that muscle H+ release would be greater for a given rate of ATP turnover without lactate production (Robergs et al. 2004).

There is no ‘evil’ to muscle lactate production. As there is no clear evidence that lactate has any direct negative effect on muscle contraction, there is also no ‘conundrum’ to muscle lactate. Muscle lactate production is essential to sustained, repeated intense muscle contraction. Post-training increases in MCT1 and MCT4 support greater rates and total capacities of muscle lactate efflux during intense exercise performance, thereby allowing for a greater capacity for muscle lactate production and related glycolytic ATP turnover. It is long overdue, based on all aspects of the scientific method, to recognize muscle lactate production as a benefit to intense exercise performance and muscle biochemistry. I encourage researchers and educators alike to present an interpretation of muscle lactate production where the evidence-based view of the benefits of lactate production are espoused rather than a traditional blame of fatigue and acidosis simply because that is how it has always been. (Robergs et al. 2004)

Thus the aches and pain in strenuous exercise exist it is an indication of muscle fatigue but the formation of lactic acid facilitates extended muscle contraction and forestalls muscle failure.

Does massage therapy “flush” lactic acid from the muscle tissue?

True or false: massage after exercise assists in the removal of lactic acid. Answer: False.

The research overwhelmingly refutes this commonly held and frequently exclaimed belief. The lactic acid debate has raged for a century, and for the past two decades the research consistently demonstrates that blood lactate will return to normal within 20-60 minutes post-exercise, regardless of intervention. Yet, massage schools continue to teach this flawed lactic acid theory and massage therapists still declare it as truth to clients and the media.

It is time to reform our declaration on the benefits of massage for clients. It is essential to stop perpetuating a fasle theory. As a result of this pervasive myth, articles are published making damaging claims about massage, such as "research questions efficacy of massage as an aid to recovery in post exercise settings" and "massage not an effective treatment for enhancing long-term restoration of post-exercise muscle strength and its use in athletic settings should be questioned." Undocumented claims, such as "massage assists in the removal of lactic acid" draw attention and will be tested. The negative results become fodder for those looking for a shocking headline.

Even if massage does not help move lactic acid, thousands of elite athletes and trainers can't be wrong when they commit valuable resources to pack up massage therapists and take them across the country on bike races, or provide precious space in the medical tents at the Olympics, or allow the female massage therapist an unprecedented seat on the bench in the San Diego Padre's dugout. Massage does work. But, in an era of open access to research and the push for evidence-informed practices, we must heed the available data and speak accurately about what we do and why it works. When we fail to do so, it comes back and bites us where it hurts. We must better understand the known physiological effects of massage and how massage benefits our clients to be able to refute gross conclusions that don't accurately reflect our role in helping athletes recover from post-exercise symptoms.

In order to better understand why the belief that massage removes lactic is false, we need to better understand blood lactate and the causes of post-exercise symptoms. The first questions to explore are: what is lactic acid or blood lactate and what does it do? If lactic acid buildup doesn't cause muscle soreness and fatigue, then what does? Does massage enhance performance, relieve muscle fatigue, and reduce muscle soreness? If so, how? What do we know about the physiological effects of massage and what has yet to be demonstrated through research?

Once we have appraised the best available information, we can reform our statements about how massage benefits clients. Then we need to encourage all massage therapists to promote the best available data on the benefits of massage to clients. Finally, it is important to inform the next generation of research to encourage questions meaningful to practitioners. We can submit questions that we confront regularly in practice, identify the theories we dispute, and hopefully provoke someone to explore potential answers. (Massage Bodywork, Diana Thompson 2011).

Conclusion

The genesis of lactic acid, lactate, in muscle cells and tissue is an integral component of muscle contraction that facilitates continued muscle use even in anaerobic muscle fatigue. The metabolic process produces lactate as a function of anaerobic combustion of glucose to continue the generation of ATP that in turn provides energy to muscle tissue for repeated contractions. This continues until muscle fatigue leads to muscle failure until the aerobic process resumes balance in the cells, that is to say in recovery.

The application of Swedish or deep pressure or contractions, massage on muscle groups or single muscle will allow the muscle to relax and recover in an enhanced state, but still in the presence of lactate. There is no scientific evidence that shows or proves that massage alone will “push out” this by-product of cellular combustion to speed muscle recovery or that compression, Swedish or deep massage will reduce lactic acid at the cellular level that leads to pain or stiffness relief. Yes, massage therapy will help the body feel better, but does not mean it mechanically reduces lactic acid content.

References:

Robergs, R. A. (2011), Nothing ‘evil’ and no ‘conundrum’ about muscle lactate production. Experimental Physiology, 96: 1097–1098. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2011.057794

Thompson, D. L. (2011). The Lactic Acid Debate. Massage and Bodywork Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.abmp.com/textonlymags/article.php?article=173.

During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that require research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Society has assumed for many decades that the application of massage holds a valuable mechanical influence on the human body's circulatory system with the truism that effleurage will directly push the blood through the arteries/veins and petrissage will force metabolites, toxins, and blood out of the muscles. With this straight-forward thinking of mechanical influence, particularly in the sports scene, it was very popular to hear that lactic acid was a waste product from exercise that caused muscle fatigue and/or delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). One of the most misconceived benefits of massage is that it helps to flush lactic acid from the muscle cells.

A few methods of research have convinced me that this removal of metabolites cannot be so mechanical. There's a quantitative approach taken by the School of Kinesiology and Health Studies, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, where "Twelve subjects performed 2 minutes of strenuous isometric handgrip (IHG) exercise at 40% maximum voluntary contraction to elevate forearm muscle lactic acid. Forearm blood flow (FBF; Doppler and Echo ultrasound of the brachial artery) and deep venous forearm blood lactate and H+ concentration ([La-], [H+]) were measured every minute for 10 minutes post-IHG under three conditions; passive (passive rest), active (rhythmic exercise at 10% maximum voluntary contraction), and a massage (effleurage and petrissage). Arterialized [La-] and [H+] from a superficial heated hand vein was measured at baseline" (Wiltshire). Through this method, it was found that massage actually impaired lactic acid removal by mechanically inhibiting the circulation of blood through the arm.

Another approach would be through qualitative research. In order to understand a complex topic, it is essential to have a qualitative breakdown of the topic that dissects the key elements of the research at hand. To understand the effects of massage on flushing lactic acid from the muscle cells, we need to observe what exactly lactic acid and lactate are, as well as the effects of massage on the muscle cells and circulation of blood. Shirley Vanderbilt, a staff writer for Massage & Bodywork Magazine, translates this question into concise explanations using references with backgrounds in Physiology, Kinesiology, Physics, and many other relevant credentials.

Vanderbilt compiles several sources to express that the body breaks down glucose into pyruvate. The muscles perform best during the initial "aerobic glycolysis" while O2 is present in the muscles. When the muscles become O2 depleted, they enter a phase of "anaerobic glycolysis" where the glucose turns to pyruvate . The pyruvate then turns to lactic acid and rapidly dissociates from its hydrogen ion to form lactate. If exertion continues while O2 is still depleted, then lactate will continue to accumulate, thus creating an acidic blood pH. This acidic environment will cause the muscle to slow down (fatigue) in order to regain O2 and to then break down glucose aerobically again. Lactate cannot be utilized by the muscle cells so it will travel through the blood on its' own and be utilized by the liver for glycogen storage. Within 30-60 minutes of ceasing exertion, lactate levels will return to normal along with blood pH levels. Research supports that the best way to flush lactic acid from the muscle cells is through active recovery such as light jogging, and that massage is no more effective than passive rest. This is not to say that massage doesn't affect the circulatory system through stimulation of the nervous system. With this information, I found that the belief, "massage flushes lactic acid from the muscle cells" to be unsupported and false. Lactic acid is an element of our metabolism that doesn' not get "worked" out but will naturally make its way out with time. I

. The pyruvate then turns to lactic acid and rapidly dissociates from its hydrogen ion to form lactate. If exertion continues while O2 is still depleted, then lactate will continue to accumulate, thus creating an acidic blood pH. This acidic environment will cause the muscle to slow down (fatigue) in order to regain O2 and to then break down glucose aerobically again. Lactate cannot be utilized by the muscle cells so it will travel through the blood on its' own and be utilized by the liver for glycogen storage. Within 30-60 minutes of ceasing exertion, lactate levels will return to normal along with blood pH levels. Research supports that the best way to flush lactic acid from the muscle cells is through active recovery such as light jogging, and that massage is no more effective than passive rest. This is not to say that massage doesn't affect the circulatory system through stimulation of the nervous system. With this information, I found that the belief, "massage flushes lactic acid from the muscle cells" to be unsupported and false. Lactic acid is an element of our metabolism that doesn' not get "worked" out but will naturally make its way out with time. I

With this information, I found that the belief "massage flushes lactic acid from the muscle cells" to be unsupported and false. Lactic acid is an element of our metabolism that doesn't get "worked" out but will naturally make its way out with time. It is especially silly to think that lactic acid even needs to leave the muscle in order for our muscular pain to cease because lactate/lactic acid has nothing to do with our DOMS! The DOMS is a side effect of micro tears in our muscle fibers. Even if lactic acid were the cause of pain produced by over-exertion, then it doesn't explain the disproportion of blood lactate to the amount of pain felt 1-2 days later as the lactate levels have retreated by then.

In my opinion, particularly with a topic of this complexity, I find that research containing a mixture of more qualitative and scientific explanatory depth, along with a smaller portion of quantitative research, is most valid. This is most true for the massage profession, because we cannot simply take someone's word on their experience with a client, or the simplistic idea that the body should react in such a way through basic means of mechanical influence. We require a deeper look in a biological and physiological perspective to understand the Krebs cycle, where lactic acid/lactate is produced, and how massage cannot simply force a metabolite out of tissue through pressure.

The criterion in which I find information to be valid is when the research is supported by scientifically accepted principles. The chemical and biological function of lactic acid through the metabolic process of glycolysis is widely understood amongst doctors; along with the physiological effect on the circulation of blood flow from the application of massage.

From this research, I have found a new spark of interest in "myth busting" massage related controversies. Massage is struggling to be seen as part of the medical field. It is because of these false truisms that the incorporation of massage into hospitals and other medical environments has been set back. I'd like to aid the progress of this incorporation by properly educating my clients with valid research and evidence.

As professionals in the massage field, it is absolutely important for us to take research in our live of work seriously. Our techniques, and knowledge that we apply to our clients, is much like the medicine prescribed by a doctor. If we aren't truly informed in our line of work, then we can easily endanger a human life, or at best, unnecessarily misinform a whole population with an idea that teaches "creative physiology."

References:

Vanderbilt, Shirley. "Peak Bodywork's Wellness Journal" Massage & Bodywork Magazine, Oct/Nov 2001, http://www.peakbodywork.com/journal/spring07.pdf

Wiltshire, E. Victoria, et al. "Massage Impairs Post Exercise Muscle Blood Flow and 'Lactic Acid' removal." Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 2009, p 1. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3181c9214f

During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that require research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Massage Therapy is a form of touch-therapy, aimed at providing relief from physical and psychological ailments. For the purposes of this essay, the massage style I am referring to is generally Swedish Massage.

In researching the statement, "Massage can spread cancer and is always contraindicated," I have found many types of articles that explore concepts and beliefs surrounding massage. These papers include randomised trials (6,8), single case studies (9), literature reviews (2,11), expert opinions (1,3,4,14), surveys (5,10,12,13), and quasi-experimental designs (7). Often, the numbers in the studies are small, reducing the power of the studies. The most valid, or strongest level of evidence, is randomised controlled trials (RCTs). There seems to be a paucity of well-designed and large scale RCTs in this field of study. Researchers have expressed the desire for further research and increasing the power and quality of the study desgins. Better quality research, and positive outcomes supporting the benefits of massage therapy, will increase the standing of massage therapy as a true evidence-based health care treatment in oncology. I have included a range of articles of variable quality, hoping to encompass both the facts about good cancer care and current professional opinion. Most of the articles have been drawn from clinical journals which suggests that they have a reasonable level of validity.

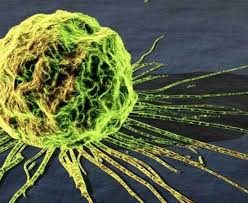

To question if the statement is true or false, one needs an understanding of what cancer is. Cancer is a disease that can take many forms. There are cancers that involve the blood (e.g. leukemias), cancers involving the musculoskeletal system (e.g. osteosarcomas), cancers involving the reproductive system (e.g. breast and prostate), and cancers involving the major organs of the body (e.g. liver, lung, colon), just to name a few. Cancer can strike anyone, of any age, of any gender and of any race. It is a disease that often results in the demise of its victim if treatment is not swift and rigorous. Cancer involves the uncontrolled division of abnormal cells, resulting in tumors within the primary tissue that can spread, or metastasize, though out bodily systems. Cancer treatment is often harsh and leaves the sufferer to deal with sequelae that can linger for years beyond the active phase of cancer treatment. There appears to be much demand for massage therapy in this population, to help relieve some of the suffering. This treatment is often sought during active cancer treatment, long after cancer treatment has ceased, and in the terminal phase of the illness (palliative care).

In researching this statement, I have explored recent articles that have investigated massage therapy given to different groups of cancer patients throughout the world, and also looked at the theories that cover tumor behaviour, and the opinion of massage experts regarding the safety of massage in this special population of massage clients.

cancer cell

I have been unable to find any recent articles that support the notion that cancer can be spread by massage. Corbin (14) reports that there is "no evidence that massage can spread cancer." As stated by MacDonald (1), it is a myth that massage can spread cancer. "The good news is that the contraindication against massage, based on the irrational fear of metastasis, is well on its way out of massage pedagogy." MacDonald goes on to point out the considerations of therapists in planning and conducting massage therapy on people with active cancer, as this condition does often dictate local contraindications to massage therapy.

Even to this day, it is not clear to researchers and practitioners how cancer spreads throughout the body. One theory (2) is that cancer cells appear to move from their primary site via blood and lymph vessels. The implication of this, in terms of massage, would be that it would be prudent to avoid any area that has active cancer tumor activity, to avoid encouraging such movement of cells from the tumor. However, there is no evidence that I have found to support the notion that massage is contraindicated if massage is conducted away from the tumor site.

Several authors have recommended that oncology massage is most safely performed by licensed massage therapists who have specific intensive training in cancer care (1,3,4,5). In terms of massaging a client with active cancer, the therapist must take precautions in providing a safe treatment. Things to consider include: the therapist should involve the client's primary cancer physician in treatment planning; the client should be screened for local contraindications, including increased risk of fractures (bone metastases or primary tumors), bleeding (anemia), infection or increased risk of neutropenia, and pain levels and location. The therapist would also screen for the standard contraindications to treatment. Therapists need a thorough understanding of what clients are dealing with while undergoing active cancer therapy (including chemotherapy and radiotherapy side effects), and what clients can continue to suffer from well after their treatment has ended.

The type of massage given to cancer patients needs to be modified. Walton (4) describes the type of massage she recommends giving during chemotherapy treatment as being gentler in pressure, slower in speed, decreased friction, modified treatment position if required, regular assessment of the client regarding day to day function and well-being, and extra care with infection control and hygiene (immunosuppression). This, along with a trained oncology massage therapist and consultation with the medical physician, will enhance safety and effectiveness of treatment. Other researchers have made similar suggestions in terms of treatment modifications (6,7,8,9).

Many studies have found that massage is beneficial in cancer patients, particularly with helping reduce pain levels (6,11,12,14), depression and anxiety (7,8,13,14), and improving a general sense of well-being and empowerment (5,10). Other benefits of massage therapy include increased relaxation (5,8,9), improved sleep (6,12), and decreased perceived abdominal bloating (7). Studies have looked at massage in both clinical and residential settings. 20% of cancer clients seek massage during and after their treatment phases (12, 13, 14).

The expert opinion of one author (3) referred to the instance where massage therapy is contraindicated in cancer clients (aside from any other contraindications, e.g. systemic illness or inflammation, acute DVT or infection), being where the therapist that has no oncology training. The author then states that massage is indicated in cancer clients in the hands of a trained oncology massage therapist, especially in cancer survivors, in consultation, again, with their medical physician.

In summary, there is no conclusive evidence to support the idea that massage spreads cancer, and there are many researchers, physicians, clients and massage therapists who advocate massage therapy as beneficial during all phases of cancer treatment. Essentially, the research I have referred to contradicts the statement "massage can spread cancer and is always contraindicated." Massage therapy is safest in this client group when provided by therapists trained in oncology massage. Cancer patients can have massage therapy safely, as long as their therapist continues to review their condition at each session, and screens for local and absolute contraindications to treatment, and modifies treatment accordingly.

What implications does this finding have for me and my practice? I am deeply interested in providing care to people with cancer. I want to be able to help relieve their suffering and educate them about the healing and recovery process. I am relieved that the statement appears to be false as I have provided massage therapy to clients in the past (both as a physiotherapist and a lymphedema therapist). In terms of my learning and future practice, I have enrolled myself in an oncology massage therapy course, to give me the tools and confidence to continue treatment for this group of clients in the safest way possible. I feel there will also be the potential for me to participate in educating other massage therapists in the future in oncology massage, and for me to consider participating in researching this area further.

Is research important in the massage profession? I believe it is. I want to have evidence based on research to support the foundations of the therapy I give to clients and to help dispel any myths that are hindering patients from receiving good and necessary care. This will boost the confidence of myself and clients and that of referring professionals. I do not want to provide treatments to clients that will either not benefit them or potentially harm them.

References:

MacDonald, G. "Massage Therapy in Cancer Care: An Overview of the Past, Present and Future." Alternative Therapies 2014 Vol 20 Suppl 2:12-15

Bockhorn, M, Jain R and Munn L. "Active versus passive mechanisms in metastasis: do cancer cells crawl into vessels or are they pushed?" Lancet Oncology 2007 May; 8(5); 444-448.

Handley, W. "Massage for Cancer Patients: Indicated or Contraindicated?" Massage Today 2007 January Vol 7 Issue 1 (www.massagetoday.com)

Walton, T. "Chemotherapy and Massage." Massage and Bodywork Magazine for theVisuallyy Impaired." May/Jun 2011 (found online www.abmp.com)

Furzer B, Petterson A, Wright K, Wallman K, Ackland T and Joske, D. "Positive patient experiences in an Australian integrative oncology centre." BMC Complementary Alternative Medicine 2014; 14:158 (published online 2014 May 14)

Toth M, Marcantonio E, Davis R et al. "Massage Therapy for Patients with Metastatic Cancer; A Pilot randomized controlled trial." Journal of Alternative Complementary Medicine 2013 Jul; 19(7); 650-656

Want T, Wang H, Yang T et al. "The Effect of Abdominal Massage in Reducing Malignant Ascites Symptoms." Research in Nursing and Health 2015, 38:51-59

Taylor A, Snyder A, Anderson J et al. "Gentle Massage Improves Disease-and Treatment-related Symptoms in Patients with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia." Journal of Clinical Trials 2014:4

Lu W, Ott M, Kennedy S et al. "Integrative Tumor Board: A case report and discussion from Dana-Farmer Cancer Institue." Integrated Cancer Therapy 2009 Sep: 8(3):235-241

Dunwoody L, Smyth A and Davidson R. "Cancer patients' experiences and evaluations of aromatherapy massage in palliative care." International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2002,8:10, 497-504

Miladinia M, Baraz S, Zarea K and Nouri E. "Massage Therapy in Patients with Cancer Pain: A review on Palliative Care." 2016. Published online Sept 27. Jundishapur J Chronic Diseases Care.

Dhanoa A, Yong T, Yeap S, Lee I and Singh V. "Complementary and alternative medicine use amongst Malaysian orthopaedic oncology patients." BMC Complementary Alternative Medicine 2014; 14: 404

Cushall S, Cha S, Ness S et al. "Symptom burden and integrative medicine in cancer survivorship." Support Care Cancer 2015 23:2989-2994

Corbin, L. "Safety and efficacy of massage therapy for patients with cancer." Cancer Control 2005 Jul 12:3

During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that requiring research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Massage therapy is a budding industry, bringing in $12.1 billion dollars in 2015 alone in the United States (AMTA, 2016). Despite being widely accepted among the general population, it is still relatively new as an accepted part of the health industry in the Western world. Part of the reason is due to lack of scientific evidence indicating the benefits of massage. However, that does not suggest that massage is not beneficial. Many studies show its positive effects on overall wellness, but they may not be of the highest scientific rigor regarding studies. Unfortunately, research in the massage realm is difficult due to the nature of the therapy itself.

Types of research found in the massage profession are case reports, pilot studies, randomized controlled trials, and meta-analyses. In my opinion, case reports are individual incidences and should not be taken as a fundamental understanding of massage outcomes. When many case studies claim the same outcome, only then does it warrant a larger study to provide evidence for, or to disprove, that effect. Even pilot studies should be applied carefully. Though randomized controlled trials are the gold standard in the scientific community, they are extremely difficult to set up in the massage world. Meta-analyses are the highest level of research to look to, but, unfortunately, many suggest there are not enough studies or not enough evidence currently to create generalizations about massage topics. With this knowledge, pilot studies can be looked at to determine validity of research, keeping in mind that staying up with the most current research becomes even more important. To determine clinical significance, there must be statistical significance. Statistical significance means that the study showed what happened in the test was a real effect and not something that happened by chance.

Research is important in the massage profession. Period. Research is vital for massage to be taken more seriously in the health field. For instance, oncology massage has taken a complete change from being totally shunned to being encouraged in cancer patients in a rather short amount of time, due to scientific research. On the other hand, many people seek out massage for the therapeutic, relaxing, and temporary relieving benefits of massage, and do not need any convincing that massage is beneficial. It is not necessary for a relaxation massage business to function, but having a practice grounded in research can only be beneficial - especially to recommend certain modalities and treatments on an individual basis. A therapist will not only gain client trust by being scientifically backed, the client will benefit from the enhanced and focused treatments stemming from massage research.

So, does deep tissue massage need to be painful to be effective? First, what is deemed "effective" in massage? Does modest, temporary relief from pain in muscles count as effective? Or must it produce long-term effects to be considered as such? As mentioned earlier, regardless of massage's research-proven effects, temporarily reducing stress and relieving muscular pain are worth it for clients that come back to the table again and again. From this perspective, I believe even short term effects are noteworthy. There is a small selection of research on massage pressure that can be assessed.

One such article of research is "Effects of Patterns of Pressure Application on Resting Electromyography During Massage," by Langdon Roberts, in which various levels of pressure were applied to muscles during rest to each participant. They received three levels of pressure in ascending or descending order on their rectus femoris muscle. Surface electromyography (EMG) was used to measure activity levels of the muscle at baseline and after each pressure level was applied. Interestingly, EMG readings did not change significantly between ascending readings, meaning the muscle stayed relaxed. Yet during descending readings, EMG readings did vary significantly "with the largest variation, an increase of 235%, noted between baseline activity and activity after deep pressure" (Roberts, 2011). This finding suggests that light- to moderate-pressure massage is necessary, before deeper pressure, to maintain relaxation in muscles. Chronic pain syndromes cause elevated nerve reflexes, and increasing pressure variation is a possible mechanism of chronic pain relief by massage therapy. This study shows that it is not beneficial to start out with deep pressure; it causes severely enhanced muscle activity which is not the desired effect. The approach of gradually increasing pressure, as currently practiced by many massage therapists, may have more therapeutic benefit that applying deep pressure with little or no warm-up.

One such article of research is "Effects of Patterns of Pressure Application on Resting Electromyography During Massage," by Langdon Roberts, in which various levels of pressure were applied to muscles during rest to each participant. They received three levels of pressure in ascending or descending order on their rectus femoris muscle. Surface electromyography (EMG) was used to measure activity levels of the muscle at baseline and after each pressure level was applied. Interestingly, EMG readings did not change significantly between ascending readings, meaning the muscle stayed relaxed. Yet during descending readings, EMG readings did vary significantly "with the largest variation, an increase of 235%, noted between baseline activity and activity after deep pressure" (Roberts, 2011). This finding suggests that light- to moderate-pressure massage is necessary, before deeper pressure, to maintain relaxation in muscles. Chronic pain syndromes cause elevated nerve reflexes, and increasing pressure variation is a possible mechanism of chronic pain relief by massage therapy. This study shows that it is not beneficial to start out with deep pressure; it causes severely enhanced muscle activity which is not the desired effect. The approach of gradually increasing pressure, as currently practiced by many massage therapists, may have more therapeutic benefit that applying deep pressure with little or no warm-up.

Research showing the effects of moderate-pressure massage are also beneficial for disproving the "no pain, no gain" approach to massage. One research analysis tells all in its title, "Moderate Pressure is Essential for Massage Therapy Effects." The abstract claims that, when moderate pressure is applied, "growth and development are enhanced in infants and stress is reduced in adults," showing that painful massage is not necessary for effective massage (Field at al., 2010). Moderate pressure is preferred for beneficial effects.

Another study, looking at massage effects on rheumatoid arthritis, showed similar results. Each of 42 volunteers were randomly assigned to a light- or moderate-pressure group. A therapist massaged their arm weekly for one month and taught each participant at-home self-massage techniques. As a result, "by the end of the one month period, the moderate pressure massage group had less pain, greater grip strength and greater range of motion in their wrist and large upper joints (Field et al., 2013)."

A review of moderate pressure massage studies contributes several positive effects of moderate pressure including the aforementioned growth in infants, reduced pain in rheumatoid arthritis, and included several more benefits from increased attention and immune function, to decreased pain in fibromyalgia. Moderate pressure massage, as compared to light pressure, reduces anxiety, depression, decreased cortisol levels (the stress hormone) and showed a relaxation response by changed EEG patterns. Moderate massage also stimulates multiple brain regions involving stress and emotional regulation, measured by functional magnetic resonance. However, the author states that, unfortunately, these studies still need to be peer-reviewed and more research is needed to identify the "underlying neurophysiological and biochemical mechanism associated with moderate pressure massage (Field, 2014)."

Pain is a protective mechanism in the body used to alert the brain of harmful stimuli, either actually or potentially, injuring the body. Pain can produce, not only physical but also emotional, responses. Painful pressure would mostly be described as an acute pain - temporary, and without lasting effects. However, reaching this state is the opposite effect of the overall intention of massage therapy. The body reacts to pain by becoming unrelaxed and potentially sending an immune response to that area of the body (The Gale Group, 2008).

Not only is painful massage unnecessary for beneficial effects, it may also be harmful. One case report observes an isolated incident in which a spinal accessory nerve was injured by deep tissue massage, causing droopy shoulder and scapular winging in the individual. In this case, not only was deep tissue massage not effective, it broke the first ethical rule of massage - do no harm (Aksoy, 2009).

Each person's body is unique to touch, and a pressure that may be painfully deep to one may not even feel of therapeutic value to another. What is it about pain that makes so many people believe this myth that massage must be painful? To compare massage to yoga and stretching, there is a level of sensation that feels intense but still feels "oh so good." Once the pressure or stretch is released, there is a sigh of relief that that movement is over, and the body falls into a more relaxed state. It feels like something good has been accomplished. This is what I would say the threshold of pressure that I am comfortable with giving during a massage session for those clients that do prefer deep pressure. Once the deep pressure makes the body go into the protective zone, that is not ok. I never want to bruise or harm a client or make their body less accepting to my touch.

In conclusion; no, deep tissue massage does not need to be painful to be effective. In fact, painful massage is less effective. The body tenses up into a protective mode, not allowing the tissues to relax to accept the works that the therapist is doing to aid in stress relief and hypertension. Using what the studies show, one can use moderate pressure to be effective and should also work from lighter to heavier pressure. As far as my own practice goes, I will use this information to apply proper therapeutic pressure. I am one of those people that typically likes especially deep pressure on my shoulders and lower back, at the threshold between intense pressure and pain. To note an especially deep pressure massage I recently received by another student, specifically deep forearm pressure applied too heavily on the calves, I tensed up. I did not enjoy it, I was brought out of my relaxed state, and my body was left bruised for a week. I will definitely carry that experience with me as I massage clients in the future. After reviewing these research findings, and having my own experience with painful pressure, my expectations in each massage I personally receive have changed. In class massages, I initially felt frustrated when the other student was not going deep enough for me. Now, with the understanding that moderate pressure is effective, I can simply relax with the understanding that a moderate-pressure massage is still working on my body's tension and stress. I have also massaged many people who prefer deep pressure already in my internship alone. I hope to steer people out of their sensation - based pressure needs and inform them that what they think they want may not necessarily provide the best outcome. I plan to listen to my client's needs regarding pressure, but also educate them about the research by communicating individually, and through my own posts on social media and my website. I will make sure to work superficial to moderate pressure and use deep pressure only if necessary, making sure to never reach a painful level. Pressure and sensation change from person to person, so I plan to check in regularly, during each massage, about pressure, making sure I never inflict pain. In all, I am happy with the question I chose to research, and am somewhat satisfied with the research I found. I wish there was more research to extract from and I am looking forward to staying current on the topic regarding pain, pressure, and effective massage.

Works Cited:

Aksoy, A., Schrader, S., Ali, M., Borovansky, J., & Ross, M. (2009, November). Spinal Accessory Neuropathy Associated with Deep Tissue Massage: A Case Report. (Abstract). Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(11), 1969-1972. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.015.

Field, T. (2014, November). Massage Therapy Research Review (Abstract). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(4), 224-229. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.07.002

Field, T., Diego, M., Delgado, J., Garcia, D., & Funk, C. (2013, May). Rheumatoid Arthritis in Upper Limbs Benefits from Moderate Pressure Massage Therapy. (Abstract). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 19(2), 101-103. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.12.001.

Field, T., Diego, M., & Hernandez-Reif, M. (2010, April 19). Moderate Pressure is Essential for Massage Therapy Effects (Abstract). International Journal of Neuroscience, 120(5), 381-385. doi:10.3109/00207450903579475.

Industry fact Sheet. (2016, February). Retrieved April 20, 2016, from https://www.amtamassage.org/infocenter/economic_industry-fact-sheet.html

Paul Ingraham. (2016, May 13). Massage Pressure: How Deep is Too Deep? Retrieved October 05, 2016, from https://www.painscience.com/articles/pressure-question.php

The Gale Group, Inc. (2008). Pain | definition of pain by Medical dictionary. Retrieved October 05, 2016, from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/pain

Roberts, L. (2011. March 30). Effects of Patterns of Pressure Application on Resting Electromyography During Massage. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork, 4(1), 4-11. Retrieved April 29, 2016, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3088531/#_ffn_sectitle