During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that require research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Based on surveys by the American Massage Therapy Association, one of the primary motivations today for people seeking massage is for health and wellness reasons (AMTA, 2017), clearly indicating that massage therapy is becoming accepted as a form of healthcare. Yet, under the umbrella of the term "massage therapy," many modalities exist that claim the ability to help lessen the discomfort of numerous conditions. The primary means that we, as a society, have to attempt to validate the claims about massage therapy is the application of scientific research methodology. However, our current system relies on large amounts of money being funneled into research for patentable substances that, if successful, provide a large financial reward to the patent-holding creator. As massage cannot be patented past a registered trademark for someone's name, limited funding is available for the research. Thankfully, though, as massage gains in popularity, there is a grassroots push for more information and continued research into various types of massage therapy.

Within scientific research there is a hierarchy of journal articles: randomized clinical trials (RCT's)-specifically, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies--are considered the "gold standard" by the medical establishment. In this type of study (ideally), the variables are stringently controlled and bias is almost completely eliminated. Then the written results undergo peer review so that any potential shortfalls in the process can be found and remedied. The goal is to create a situation in which the experiment can be duplicated by any other researcher, thus confirming the findings and verifying that the results apply to the majority, that is, that the results are statistically significant to a specific percentage of a group and that the results are not random.

There are a number of other types of research articles that rank "below" the RCT but are still considered valid research (and are accepted into the peer-review process of a journal), or are at least indicative of an area of continued study and where RCT's should be designed and undertaken. These include systematic reviews, cohort studies, case-control studies, case reports and pilot studies. Today, due to the efforts of many people, a quick search for "massage therapy" in PubMed shows a large variety of these types of articles, although some modalities and some types of research have received much more attention than others, and some modalities lend themselves to the scientific process more readily than others.

I believe that all of these types of studies are valid when looking for studies to expand our understanding of how massage works and what we should offer our clients, as long as we understand that nothing will ever be one hundred percent effective. Ultimately, there is no perfect piece of research. That's the one true absolute in scientific analysis. The "gold standard" is based on statistical analyses that calculate how the experiment affects the group or cohort. It's impossible to run an experiment on the entire population of the planet. By design and definition, a study has to be performed on a representative group, and even then the goal is to find a "treatment" that affects the majority of the group rather than all of the group, because there will always be "outliers": those who don't respond when it is effective for the majority, or those who will be affected when the majority aren't. In other words, statistics deal with group results while the individual is concerned about the response of themselves or their loved ones. This is the fundamental struggle in utilizing research in providing services for individuals.

However, all of these types of research work well together: case studies build case reports that can then be built into case-control studies. When the subjects are followed for a period of time, a cohort study is produced. Pilot studies initiate work into new sub-areas and systematic reviews look at the results of various studies. All of these together build a comprehensive understanding of an area as well as point to new experiments to pursue. It all adds to our knowledge base and I believe that's the best result.

Given that research about massage therapy is increasing, it would probably be wise for any therapist who wishes to be involved in research to take a "Statistics for the Social Sciences" type class at a local community college or university. It makes understanding research abstracts much easier, as well as assisting the therapist in spotting the weaknesses in writing about new research that is very common in today's internet connected world. In an ideal world, there would be many RCT's with cohorts numbering in the thousands, but given the realities of research, I'm happy when they number over fifty. I also find case studies very interesting precisely because they discuss how one person was helped with a specific treatment and that's where research starts.

As massage therapy encompasses so many modalities, and the technological advances in various forms of diagnostics and measurements continue at a brisk pace, I believe that research in massage therapy will continue to grow. It expands our knowledge of what we do and how we can assist our clients in their goals. It also furthers the standing of massage therapy as a method of health care. As there are still those who criticize and "debunk" various aspects of massage therapy, rightly or wrongly, research is necessary to find the truth.

In examining the statement "ischemic compression for trigger points should be done as deep and hard as possible" with regard to current research, it's useful to look at the verity of the statement first. My first concern about this statement is that it's an absolute. While the word "always" is not in the sentence, it's implied. As I mentioned earlier, absolute statements about the care of others are dangerous as they are unprovable, and adhering to blanket statements about the care of individuals makes you blind to possible exceptions, which in turn leaves you open to charges of client neglect. Secondly, trigger points, by definition, are  "hyperirritable:" they're painful when subjected to pressure, one of the diagnostic criteria as listed in Travell and Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, the authoritative work in the field. If a massage therapist simply puts as much pressure on a trigger point as is possible, it hurts. The therapist can also activate the nociceptive reflexes of their client which will cause the client to tense up and pull away as they attempt to protect themselves. This can result in the loss of the client at least, as well as potentially injuring a client, both situations that an ethical therapist hopes to avoid. So, the statement is questionable to begin with.

"hyperirritable:" they're painful when subjected to pressure, one of the diagnostic criteria as listed in Travell and Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, the authoritative work in the field. If a massage therapist simply puts as much pressure on a trigger point as is possible, it hurts. The therapist can also activate the nociceptive reflexes of their client which will cause the client to tense up and pull away as they attempt to protect themselves. This can result in the loss of the client at least, as well as potentially injuring a client, both situations that an ethical therapist hopes to avoid. So, the statement is questionable to begin with.

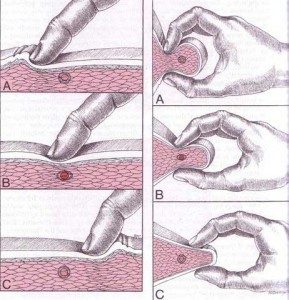

But in looking at available research studies on ischemic compression and trigger points, there does seem to be agreement on how to apply ischemic compression, although what's used in the papers I've read is something of a combination of what's suggested by Simons and Travell. In the 1st edition of The Trigger point Manual, published in 1983, both ischemic compression and deep stroking massage are mentioned as possible manual treatments for trigger points, and in a 1987 monograph Simons repeats that "pressure is applied directly on the spot of greatest tenderness (the TP) with a steady moderately painful (tolerable) pressure." This is to be held for 15 seconds to one minute (Simons, 1987). It is perhaps the reading of this that encouraged some therapists to adopt a use of "as deep and hard as possible" even though, in my opinion, that would be a misinterpretation given the words "moderately" and "tolerable."

However, in the 2nd edition of the Trigger Point Manual, published in 1999, their recommendations change, even stating that they prefer to call it "trigger point release therapy" rather than ischemic compression, and it's described as a "barrier resistance technique" to underscore a more moderate approach (Simons et al., 1999). They recommend that the therapist use a moderate pressure on the center of the trigger point until the therapist encounters a resistance that they label "the barrier." The pressure is held until the resistance decreases somewhat, and then the pressure is increased until it again meets the barrier. Again this is maintained until the barrier releases or "let's go" under the finger. This technique is specifically recommended because it is painless (Simons et al., 1999). Again, there is nothing here to suggest "as hard and deep as possible."

When looking at several studies completed since the publication of the 2nd edition, the accepted technique for applying ischemic compression seems to be somewhere in the middle of these two techniques. Generally speaking, the practitioner would apply pressure to the center of the trigger point until pain was first felt, usually described by the participant as a 7 on a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 being the most painful. The pressure was held until an initial decrease in discomfort was experienced, then the pressure was increased to the tolerance threshold again and held until there was another decrease in discomfort, usually from 15-90 seconds (Abu Taleb et al., 2016, Cagnie at al., 2013, de las Penas et al., 2006).

A pilot study comparing the effects of ischemic compression and transverse friction massage on active and latent trigger points on a study group of forty people, published in 2006, utilized this procedure for the ischemic compression part of their testing. This was compared to transverse friction applied slowly with pressure that created a tolerable pain for 3 minutes. Interestingly, both methods achieved statistically significant results based on measurement of the decrease in the pain pressure threshold (PPT) (de las Penas et al., 2006).

A cohort study in 2013 that followed the treatment of nineteen office workers treated with ischemic compression for upper trapezius trigger points for 8 sessions over 4 weeks (2 sessions per week), utilized the same protocol. At the end of the 4 weeks/8 sessions there was a statistically significant decrease in the PPT as well as at a 6-month follow-up, and there was also a significant increase in mobility and strength (Cagnie et al., 2013).

More recently a clinical study was completed that examined the results of manual pressure release (ischemic compression) compared to that delivered by an algometer with sham ultrasound as the control (Abu Taleb et al., 2016). Instead of just using the algometer to measure the pre- and post-treatment PPT they also used it (with the addition of a piece of cloth for comfort) to administer the manual pressure release to the trigger point (the APR group) along with sham ultrasound. The second group received similar treatment from a trained therapist (the MPR group) along with sham ultrasound while the third group (the US group) only received the sham ultrasound. While there was no significant difference between the 3 groups post-treatment for the PPT, the APR group had a statistically significant increase in passive side-bending range of motion.

While all three of these studies seem to indicate that manual pressure release (ischemic compression) has positive results for trigger point treatment, there are other studies that show less consistent results. However, what all of these studies do indicate is that the accepted protocol of ischemic compression on trigger points is to apply pressure to the trigger point to a level of tolerable pain for the client, hold until that decreases, then increase and hold again until another decrease occurs, and then repeat the procedure another 1-2 times to equal 90 seconds. Not one of these experiments utilizes ischemic compression that is "as deep and hard as possible."

When Dr. Janet Travell and Dr. David Simons first published their Trigger Point Manual in 1983, it was an effort to create a compendium of their work and research into the treatment of trigger point pain. Primarily meant as a resource for physicians and physical therapists, it mainly discusses the use of methods such as trigger point injection and "stretch and spray" that can easily be employed in office settings. However, their mention of ischemic compression as a manual therapy really opened the door to the therapuetic use of massage in this area, given how many people dislike needles. And, while the research into manual pressure release as a viable means to treat trigger points is somewhat limited, as most of the research examines dry needling and injections, I believe the existing research indicates that it's at least of some value. However, I also think that it's very important to use the protocol that is consistently recommended and used by these research articles in only applying pressure to a tolerable level of pain rather than following the mandate that it "should be done as deep and hard as possible."

References:

Abu Taleb W., Rehan Youssef, A. and Saleh, A. (2016) "The effectiveness of manual versus algometer pressure release techniques for treating active myofascial trigger points of the upper trapezius," J Bodyw Mov Ther, 20(4), pp. 863-869.

AMTA (2017) Massage Therapy Industry Fact Sheet: American Massage Therapy Association. Available at: https://www.amtamassage.org/infocenter/economic_industry-fact-sheet.html (Accessed: May 16 2017)

Cagnie, B., Dewitte, V., Coppieters, I., Van Oosterwijck, J., Cools, A. and Danneels, L. (2013) "Effect of ischemic compression on trigger points in the neck and shoulder muscles in office workers: a cohort study," J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 36(8), pp. 482-9.

de las Penas, C.F., Alonso-Blanco, C., Fernandez-Carnero, J., and Miangolarra-Page, J. (2006) "The immediate effect of ischemic compression technique and transverse friction massage on tenderness of active and latent myofascial trigger points: a pilot study," Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 10(1), pp. 3-9.

Simons, D.G. 1987. Myofascial Pain Syndrome Due to Trigger Points. In: Association, I.R.M. (ed). Gebauer.

Simons, D.G., Travell, J.G., and Simons, L.S. (1999) Travell & Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: the Trigger Point Manual. 2nd edn. (2 vols). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

During the course of attending massage school at A New Beginning School of Massage, students are given a number of assignments that requiring research and writing. Some of these assignments result in very insightful and well thought out information and decision-making outcomes. I am happy to share some of their assignments for you to enjoy.

Massage therapy is a budding industry, bringing in $12.1 billion dollars in 2015 alone in the United States (AMTA, 2016). Despite being widely accepted among the general population, it is still relatively new as an accepted part of the health industry in the Western world. Part of the reason is due to lack of scientific evidence indicating the benefits of massage. However, that does not suggest that massage is not beneficial. Many studies show its positive effects on overall wellness, but they may not be of the highest scientific rigor regarding studies. Unfortunately, research in the massage realm is difficult due to the nature of the therapy itself.

Types of research found in the massage profession are case reports, pilot studies, randomized controlled trials, and meta-analyses. In my opinion, case reports are individual incidences and should not be taken as a fundamental understanding of massage outcomes. When many case studies claim the same outcome, only then does it warrant a larger study to provide evidence for, or to disprove, that effect. Even pilot studies should be applied carefully. Though randomized controlled trials are the gold standard in the scientific community, they are extremely difficult to set up in the massage world. Meta-analyses are the highest level of research to look to, but, unfortunately, many suggest there are not enough studies or not enough evidence currently to create generalizations about massage topics. With this knowledge, pilot studies can be looked at to determine validity of research, keeping in mind that staying up with the most current research becomes even more important. To determine clinical significance, there must be statistical significance. Statistical significance means that the study showed what happened in the test was a real effect and not something that happened by chance.

Research is important in the massage profession. Period. Research is vital for massage to be taken more seriously in the health field. For instance, oncology massage has taken a complete change from being totally shunned to being encouraged in cancer patients in a rather short amount of time, due to scientific research. On the other hand, many people seek out massage for the therapeutic, relaxing, and temporary relieving benefits of massage, and do not need any convincing that massage is beneficial. It is not necessary for a relaxation massage business to function, but having a practice grounded in research can only be beneficial - especially to recommend certain modalities and treatments on an individual basis. A therapist will not only gain client trust by being scientifically backed, the client will benefit from the enhanced and focused treatments stemming from massage research.

So, does deep tissue massage need to be painful to be effective? First, what is deemed "effective" in massage? Does modest, temporary relief from pain in muscles count as effective? Or must it produce long-term effects to be considered as such? As mentioned earlier, regardless of massage's research-proven effects, temporarily reducing stress and relieving muscular pain are worth it for clients that come back to the table again and again. From this perspective, I believe even short term effects are noteworthy. There is a small selection of research on massage pressure that can be assessed.

One such article of research is "Effects of Patterns of Pressure Application on Resting Electromyography During Massage," by Langdon Roberts, in which various levels of pressure were applied to muscles during rest to each participant. They received three levels of pressure in ascending or descending order on their rectus femoris muscle. Surface electromyography (EMG) was used to measure activity levels of the muscle at baseline and after each pressure level was applied. Interestingly, EMG readings did not change significantly between ascending readings, meaning the muscle stayed relaxed. Yet during descending readings, EMG readings did vary significantly "with the largest variation, an increase of 235%, noted between baseline activity and activity after deep pressure" (Roberts, 2011). This finding suggests that light- to moderate-pressure massage is necessary, before deeper pressure, to maintain relaxation in muscles. Chronic pain syndromes cause elevated nerve reflexes, and increasing pressure variation is a possible mechanism of chronic pain relief by massage therapy. This study shows that it is not beneficial to start out with deep pressure; it causes severely enhanced muscle activity which is not the desired effect. The approach of gradually increasing pressure, as currently practiced by many massage therapists, may have more therapeutic benefit that applying deep pressure with little or no warm-up.

One such article of research is "Effects of Patterns of Pressure Application on Resting Electromyography During Massage," by Langdon Roberts, in which various levels of pressure were applied to muscles during rest to each participant. They received three levels of pressure in ascending or descending order on their rectus femoris muscle. Surface electromyography (EMG) was used to measure activity levels of the muscle at baseline and after each pressure level was applied. Interestingly, EMG readings did not change significantly between ascending readings, meaning the muscle stayed relaxed. Yet during descending readings, EMG readings did vary significantly "with the largest variation, an increase of 235%, noted between baseline activity and activity after deep pressure" (Roberts, 2011). This finding suggests that light- to moderate-pressure massage is necessary, before deeper pressure, to maintain relaxation in muscles. Chronic pain syndromes cause elevated nerve reflexes, and increasing pressure variation is a possible mechanism of chronic pain relief by massage therapy. This study shows that it is not beneficial to start out with deep pressure; it causes severely enhanced muscle activity which is not the desired effect. The approach of gradually increasing pressure, as currently practiced by many massage therapists, may have more therapeutic benefit that applying deep pressure with little or no warm-up.

Research showing the effects of moderate-pressure massage are also beneficial for disproving the "no pain, no gain" approach to massage. One research analysis tells all in its title, "Moderate Pressure is Essential for Massage Therapy Effects." The abstract claims that, when moderate pressure is applied, "growth and development are enhanced in infants and stress is reduced in adults," showing that painful massage is not necessary for effective massage (Field at al., 2010). Moderate pressure is preferred for beneficial effects.

Another study, looking at massage effects on rheumatoid arthritis, showed similar results. Each of 42 volunteers were randomly assigned to a light- or moderate-pressure group. A therapist massaged their arm weekly for one month and taught each participant at-home self-massage techniques. As a result, "by the end of the one month period, the moderate pressure massage group had less pain, greater grip strength and greater range of motion in their wrist and large upper joints (Field et al., 2013)."

A review of moderate pressure massage studies contributes several positive effects of moderate pressure including the aforementioned growth in infants, reduced pain in rheumatoid arthritis, and included several more benefits from increased attention and immune function, to decreased pain in fibromyalgia. Moderate pressure massage, as compared to light pressure, reduces anxiety, depression, decreased cortisol levels (the stress hormone) and showed a relaxation response by changed EEG patterns. Moderate massage also stimulates multiple brain regions involving stress and emotional regulation, measured by functional magnetic resonance. However, the author states that, unfortunately, these studies still need to be peer-reviewed and more research is needed to identify the "underlying neurophysiological and biochemical mechanism associated with moderate pressure massage (Field, 2014)."

Pain is a protective mechanism in the body used to alert the brain of harmful stimuli, either actually or potentially, injuring the body. Pain can produce, not only physical but also emotional, responses. Painful pressure would mostly be described as an acute pain - temporary, and without lasting effects. However, reaching this state is the opposite effect of the overall intention of massage therapy. The body reacts to pain by becoming unrelaxed and potentially sending an immune response to that area of the body (The Gale Group, 2008).

Not only is painful massage unnecessary for beneficial effects, it may also be harmful. One case report observes an isolated incident in which a spinal accessory nerve was injured by deep tissue massage, causing droopy shoulder and scapular winging in the individual. In this case, not only was deep tissue massage not effective, it broke the first ethical rule of massage - do no harm (Aksoy, 2009).

Each person's body is unique to touch, and a pressure that may be painfully deep to one may not even feel of therapeutic value to another. What is it about pain that makes so many people believe this myth that massage must be painful? To compare massage to yoga and stretching, there is a level of sensation that feels intense but still feels "oh so good." Once the pressure or stretch is released, there is a sigh of relief that that movement is over, and the body falls into a more relaxed state. It feels like something good has been accomplished. This is what I would say the threshold of pressure that I am comfortable with giving during a massage session for those clients that do prefer deep pressure. Once the deep pressure makes the body go into the protective zone, that is not ok. I never want to bruise or harm a client or make their body less accepting to my touch.

In conclusion; no, deep tissue massage does not need to be painful to be effective. In fact, painful massage is less effective. The body tenses up into a protective mode, not allowing the tissues to relax to accept the works that the therapist is doing to aid in stress relief and hypertension. Using what the studies show, one can use moderate pressure to be effective and should also work from lighter to heavier pressure. As far as my own practice goes, I will use this information to apply proper therapeutic pressure. I am one of those people that typically likes especially deep pressure on my shoulders and lower back, at the threshold between intense pressure and pain. To note an especially deep pressure massage I recently received by another student, specifically deep forearm pressure applied too heavily on the calves, I tensed up. I did not enjoy it, I was brought out of my relaxed state, and my body was left bruised for a week. I will definitely carry that experience with me as I massage clients in the future. After reviewing these research findings, and having my own experience with painful pressure, my expectations in each massage I personally receive have changed. In class massages, I initially felt frustrated when the other student was not going deep enough for me. Now, with the understanding that moderate pressure is effective, I can simply relax with the understanding that a moderate-pressure massage is still working on my body's tension and stress. I have also massaged many people who prefer deep pressure already in my internship alone. I hope to steer people out of their sensation - based pressure needs and inform them that what they think they want may not necessarily provide the best outcome. I plan to listen to my client's needs regarding pressure, but also educate them about the research by communicating individually, and through my own posts on social media and my website. I will make sure to work superficial to moderate pressure and use deep pressure only if necessary, making sure to never reach a painful level. Pressure and sensation change from person to person, so I plan to check in regularly, during each massage, about pressure, making sure I never inflict pain. In all, I am happy with the question I chose to research, and am somewhat satisfied with the research I found. I wish there was more research to extract from and I am looking forward to staying current on the topic regarding pain, pressure, and effective massage.

Works Cited:

Aksoy, A., Schrader, S., Ali, M., Borovansky, J., & Ross, M. (2009, November). Spinal Accessory Neuropathy Associated with Deep Tissue Massage: A Case Report. (Abstract). Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(11), 1969-1972. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.015.

Field, T. (2014, November). Massage Therapy Research Review (Abstract). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(4), 224-229. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.07.002

Field, T., Diego, M., Delgado, J., Garcia, D., & Funk, C. (2013, May). Rheumatoid Arthritis in Upper Limbs Benefits from Moderate Pressure Massage Therapy. (Abstract). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 19(2), 101-103. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.12.001.

Field, T., Diego, M., & Hernandez-Reif, M. (2010, April 19). Moderate Pressure is Essential for Massage Therapy Effects (Abstract). International Journal of Neuroscience, 120(5), 381-385. doi:10.3109/00207450903579475.

Industry fact Sheet. (2016, February). Retrieved April 20, 2016, from https://www.amtamassage.org/infocenter/economic_industry-fact-sheet.html

Paul Ingraham. (2016, May 13). Massage Pressure: How Deep is Too Deep? Retrieved October 05, 2016, from https://www.painscience.com/articles/pressure-question.php

The Gale Group, Inc. (2008). Pain | definition of pain by Medical dictionary. Retrieved October 05, 2016, from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/pain

Roberts, L. (2011. March 30). Effects of Patterns of Pressure Application on Resting Electromyography During Massage. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork, 4(1), 4-11. Retrieved April 29, 2016, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3088531/#_ffn_sectitle